Why Andrew Yang is Right About Robots,

Wrong about Basic Income

By John F. Wasik

While I’m unsure about Andrew Yang’s proposal for universal basic income, he’s right about one thing: Automation is ravaging the global workforce.

Although most of us are focused on the turmoil in Washington, climate change, California wildfires or the travails of daily life, the massive evaporation of decent jobs is happening now — and will accelerate.

This is not some conspiracy theory. Some 4 million jobs have already been lost in manufacturing. And with advances in machine learning and artificial intelligence, millions of white-collar jobs are targeted for elimination. All told, some 73 million jobs could disappear by 2030, reports the McKinsey Institute.

No less than three highly respected studies have predicted that up to half of the workforce will be automated within the next 30 years. According to McKinsey, “in about 60% of occupations, at least one-third of the constituent activities could be automated, implying substantial workplace transformations and changes for all workers.”

Moreover, many researchers have not fully examined the total impact of new technologies like self-driving vehicles or automated supply chains, developments that imperil millions of high-paying blue-collar — and white collar — jobs.

I’ve researched the rise of automation and have seen how hundreds of thousands of eliminated positions in nearly every industry have been triggered by automation. Steel mills that used to employ tens of thousands of workers now employ only hundreds. In media, the silent, machine writing of some one billion press releases annually and automated reporting has replaced thousands of jobs.

Those in occupations that involve automated repetition or analysis are imperiled. Forms and basic back-office services can be automated. Machines can read, store and interpret anything from facial images and documents to X-Rays. Virtually anything on paper that can be scanned, stored, sorted and analyzed is part of this new wave of automation.

What can we do to offset the rise of the robots? Focus our educational system on promoting purely human skills: Emotional intelligence, communication, collaboration and “big picture” skeptical thinking.

Who fares best in the hyper-automation age? On the big-picture end of the work spectrum, industrial designers, engineers, urban planners and enlightened policymakers will do well.

We will also still need skilled diplomats, teachers, mental health professionals and caregivers. With some 10,000 Baby Boomers turning 65 every day, this growing segment of the labor force is essential, but is grossly under-paid or voluntary.

Granted, the growth in AI and integrated, digital manufacturing will also create new jobs. After all, we’ll need a trained workforce to program, build and fix robots and automation systems. Professions that design factories and supply-chain networks will thrive.

Yet any job that involves a machine-oriented task with raw data, paperwork, middle management and spreadsheet analysis is in trouble. Employers are always looking to reduce their head count and labor expenses. Robots, after all, don’t belong to unions, ask for fringe benefits or overtime — at least not now.

In short, we need a policy plan that helps people become what I call a“Quad I,” that is, lifelong learners who have a mastery of innovation, integration, insight, and improvisation. We need to be able to think on our feet and apply unique insights to fix global problems like climate change; increased food and water supplies; end needless wars and address massive human migration. More than ever, we’ll need to communicate and collaborate.

Are we prepared for the latest wave of automation? There’s no cohesive national or global policy that addresses the massive job dislocation to come. While groups like the World Economic Forum have addressed the issue, there certainly needs to be a broad safety net that involves retraining, integrated education and transitional assistance.

Fortunately, we have a minor jump start on developing these powerful human aspects of creativity. Most major business schools are affiliated with “incubators” and “accelerators” that drive innovative new enterprises. The “maker” movement encourages hands-on invention with modern digital tools. Modern manufacturing integrates humans with new processes. Even thousands of public libraries have added “maker spaces” with 3-D printers, laser cutters and sewing machines so that anyone can design and make things again.

Unfortunately, neither government nor our modern educational system are prepared for extensive automation. We’re still relentlessly drilling students through standardized tests, which don’t even measure what you need to succeed in a highly automated workplace. “Standardized tests are a very poor measurement of human worth and potential no matter how much you adjust them,” Yang stated in a recent tweet.

In lieu of a solid national policy framework, Yang is offering his $1,000-a-month basic income plan to provide a cushion for those dislocated by automation. I’m skeptical, though, on whether this is the right policy solution, because it sounds more like a desperate measure and doesn’t address our deep-seated need for labor in its many forms.

Although Yang’s idea sounds like a basic safety net, it doesn’t address the powerful human need to find purpose in labor. Machines may never have this conscious desire, but we will. If we don’t address this issue in a comprehensive way, we will be facing more than an employment crisis — it will be spiritual as well.

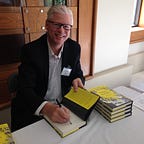

John F. Wasik is the author of Winning in the Robotic Workplace: How to Prosper in the Automation Age (Praeger, 2019), from which this essay is adapted, and 17 other books. He is a journalist, speaker and commissioner in Lake County, Illinois.